The autumn of 2010 was a tough time for the News of the World. For more than a year, the Guardian had been exposing the crimes committed by some of the newspaper’s journalists. On 1st September, the New York Times published new evidence including a devastating on-the-record interview with the former showbusiness reporter Sean Hoare implicating his editor, Andy Coulson, in phone hacking.

On 6th September, the pressure intensified when actor Sienna Miller threatened to sue the newspaper. In her letter before action, Miller’s lawyer, Mark Thomson, identified other senior journalists who were alleged to have been involved as well as Coulson and—crucially—Thomson put the newspaper on notice that it must preserve any evidence that could be relevant to the case.

Nevertheless, over the following weeks, Rupert Murdoch’s UK company, News Group Newspapers (NGN), supervised the deletion of more than four million old emails, incidentally wiping out almost all of Hoare’s career at the paper. The company removed from the newsroom nine boxes containing paperwork and audio recordings—none of which has ever been seen again—and then went ahead with a programme to destroy dozens of old computers, including those used by all of the journalists who were named in Miller’s claim.

We now know this and a great deal more about what the Murdoch company was doing as its crimes were being exposed because, since the climax of the scandal 10 years ago, key figures have changed sides and given sworn evidence; and a stream of victims have sued, forcing the company to disclose a wealth of internal records. Some of the new evidence has been deployed in open court, where it is available to be reported. Almost all of it has been overlooked by Fleet Street. This article lays out some of the new evidence in the context of the facts that previously emerged through select committees, the courts and the Leveson inquiry.

Much of the new evidence deals with allegations of the concealment and destruction of evidence. Documents submitted to court by the claimants suggest that, as the hacking victims and the police closed in, the company indulged in “fraudulent conspiracy, and/or dishonesty, bad faith and sharp practice”.

We can now see in fine detail how, in the five months after Miller issued her threat, wave after wave of deletions wiped some 30m emails from the company servers; all the emails and the hard drive of Murdoch’s UK chief executive, Rebekah Brooks, were destroyed or lost; some evidence was removed from a room in Murdoch’s HQ in east London where police had stored it until they had time to examine it; and other evidence was hidden in a secret underfloor safe in Brooks’s office.

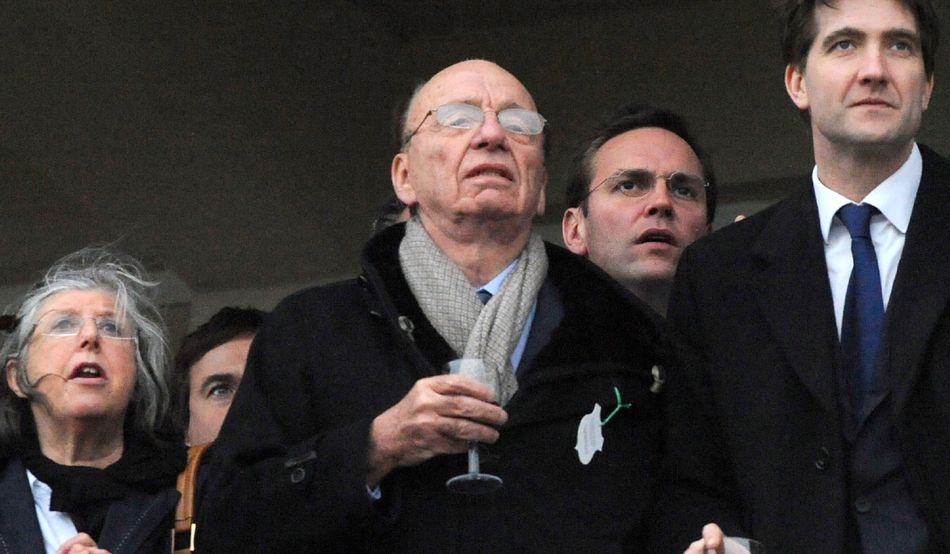

Court papers allege that named executives including Rupert Murdoch, James Murdoch and Brooks went on to mislead or lie to parliament as well as to the inquiry—led by Lord Justice Leveson—that was established once the scandal came to light to examine the culture, practices and ethics of the press. The Murdoch company lawyers do not admit to this allegation.

It is important to say that while the Murdoch company has now settled with more than 1,300 claimants and paid out an estimated £1.2bn in damages and professional fees, it continues to insist that it has not engaged in any destruction or concealment with the intention of covering up crime. It says that the deletion of emails was necessary because the servers were overloaded; paperwork and other material was cleared out in the natural course of running a crowded newsroom; computers were due to be destroyed and replaced because they were moving to a new building. It denies making any statements that it knew to be false and accuse some claimants of trying to misuse the courts “as a vehicle for wider campaigning interests against the tabloid press.” In a statement to Prospect, a spokesperson for the Murdoch company said the claimants’ allegations “have nothing to do with seeking compensation for victims of phone hacking or unlawful information gathering and should be viewed with considerable caution not only in relation to their veracity but also in the light of those who are behind them. Lawyers for the claimants work with a group of former phone hackers and employ anti-press campaigners and activists who seek to use the compensation claims to make allegations in circumstances they are protected in doing so [sic] by open justice principles.”

The evidence is clear that, from at least 1994, when its journalists first started using criminal methods to obtain information, the Murdoch company hid the wrongdoing behind a wall of secrecy. The claimants have uncovered 37 different aliases which were being used in internal records to conceal the identities of private investigators (PIs) who were potentially breaking the law for the News of the World.

Some of them were paid routinely in cash via branches of Thomas Cook. The PI who led the phone hacking, Glenn Mulcaire, was disguised as “Paul Williams”, “John Jenkins” and “Mr Alexander”. His contract dishonestly specified only lawful work, and his generous retainer payments were separated from his identity by diverting the money through five different front companies.

There was a similarly devious approach to concealing the work of Dan Evans, a professional reporter who was hired to hack in addition to Mulcaire. He eventually cooperated with police and described, for example, how, having accessed a voicemail which Sienna Miller had left for Daniel Craig, he was told by his editor, Andy Coulson, to record it on an audio cassette and then to post the cassette from outside the building back to the newsroom, so that they could pretend it had simply arrived uninvited from an unknown source.

During the first decade of the News of the World’s crimes, the new evidence suggests that the secrecy was jeopardised just once, in April 2004, when a London law firm directly challenged the paper on behalf of two clients to disclose “any ‘PIN’ or other numbers allowing access to our client’s voicemail”. The paper’s legal department settled the case out of court, and the company then concealed the paperwork for 16 years, until—finally—it was forced to disclose it to the claimants in May 2020.

So confident was the News of the World that it could keep its secrets that, according to the new material, there were two occasions when the legal department not only concealed the newspaper’s criminal methods, but also hired private investigators who specialised in using those methods to spy on people who were suing it.

The wall of secrecy was hit by a wrecking ball in August 2006, when detectives arrested Mulcaire and the paper’s royal correspondent, Clive Goodman. On the day of the arrest, police were physically obstructed when they tried to search Goodman’s desk and the accounts department. There was then, according to claimant documents, “a general clearing of desks at the NoW and documentary evidence/phone lists were disposed of”. The claimants allege that senior executives who knew about the scale of crime at the paper then “took -deliberate steps to suppress, conceal or lie… in the hope that they could preserve the (wholly false and dishonest) impression that such activities were confined simply to one ‘rogue’ journalist”.

The claimants have obtained an internal police document titled “Report To Assist Crown Prosecutor Re Rogue Reporter Cover-Up”. Although the contents have not been made public, it has been disclosed in summary that it includes details of two crisis meetings in the days after the arrests at which, according to the claimants, Coulson, his deputy Neil Wallis and his managing editor Stuart Kuttner, “started planning and executing a strategy to limit the police investigation”.

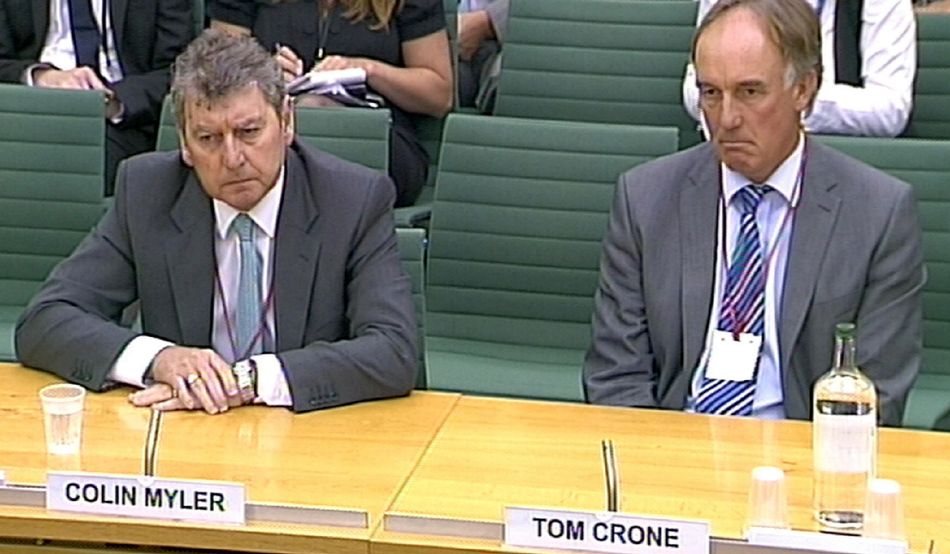

Internal emails now disclose the News of the World’s in-house lawyer, Tom Crone, telling Coulson and Wallis how they should reply to a police request for a list of evidence: “I think we should be offering very little… There are no work records for tasks accomplished by Mulcaire and we do not wish to give the police a list of journalists who had dealings with him or a list of the ‘subjects’ he worked on.” Eight News of the World journalists would be convicted of hacking with Mulcaire, and the police would reveal that he had targeted 6,349 “subjects”.

The new evidence shows that, at some point, the internal records of Mulcaire’s work were almost obliterated: the mass of emails that he had exchanged with journalists were subject to “targeted deletions… [to] conceal the scale and type of the wrongdoing”. Only 60 of them escaped the cull. Paperwork similarly was unavailable. Through its lawyers, the Murdoch company finally told the police that it had been able to find only one piece of paper in relation to Mulcaire. He had been working for them full-time for six years. Meanwhile, Coulson instructed his PA to “start printing off my draft emails—very discreetly—and storing them please”.

The police report on the “Rogue Reporter Cover-Up” includes sections on “securing [the] silence” of both Mulcaire and Goodman. Internal records show both men threatening to tell the truth, as well as the company pressuring them to plead guilty and then promising to reward both of them if they stayed silent: Mulcaire with a pay-off and Goodman with a job.

The company also supplied a letter for the court that reinforced the false claim that Mulcaire’s regular retainer was for legitimate work. This gave him an incentive to cooperate, protecting him from a confiscation order because income from lawful work would be safe. It also gave police a reason not to investigate all the journalists who had tasked him.

In January 2007, Goodman and Mulcaire were sentenced to short prison terms, saying nothing to cause trouble for the Murdoch company. Coulson resigned as editor, condemning Goodman’s crimes as “entirely wrong”, while saying nothing, as the claimants put it, of “his clear personal knowledge and involvement in these illegal activities (as well as his awareness of how many other journalists had also been engaged in them)”.

The secrecy briefly threatened to collapse when Goodman emerged from prison, complaining bitterly that instead of being given the promised job, he had been sacked. He was given £243,000—“paid off for his silence”, as the claimants put it in court. Mulcaire similarly complained, but was given only £80,000 in exchange for signing an agreement not “thereafter to make any statement or comment which might injure, damage or impugn the good name, character or reputation of NGN.”

For four more years, the Murdoch company continued to stand by the claim that Goodman was the only reporter involved with crime. Based on the available evidence, the claimants now specifically accuse both Rupert Murdoch and his son James, as well as Rebekah Brooks and her predecessor as Murdoch’s UK chief executive, Les Hinton, of dishonestly “promulgating the One Rogue Reporter narrative” to “the Press Complaints Commission, the public, the Leveson Inquiry and/or Parliament”, adding that “they knew [these statements] to be false at the time”. They also accuse them of lying to Lord Justice Leveson’s inquiry about what they had known. The in-house lawyer Tom Crone has since admitted that he always knew that the “one rogue reporter” story was untrue.

On Wednesday 8th July 2009, the Guardian revealed that NGN had paid more than £1m to settle cases with the head of the Professional Footballers’ Association, Gordon Taylor, and two associates, which threatened to reveal the true scale of criminality at the News of the World. On Friday 10th July, the Murdoch company put out a statement denying almost every detail of the Guardian story, and Brooks wrote to parliament’s media select committee accusing the Guardian of having “substantially and likely deliberately misled the British public”. The claimants say that the denial was “false in almost every respect”. Behind the scenes, the evidence reveals that on the following day, Saturday 11th July, the News of the World’s chief reporter, Neville Thurlbeck, broke ranks.

According to a statement to police from the new editor, Colin Myler, Thurlbeck that day told him and Crone that, in 2004, he personally had hacked the voicemail of the then home secretary, David Blunkett; and that he had discussed this at the time with Coulson, Wallis and Kuttner, who had instructed him to destroy his computers to conceal the hacking. Myler dictated a summary of Thurlbeck’s claims to his deputy editor, whose handwritten notes have been disclosed. Nevertheless, Myler on the next day published in the News of the World a leader comment that damned the Guardian story.

Myler told police that when he reported Thurlbeck’s claims to Brooks, she told him, “I will not let this company go into meltdown,” and something to the effect of “We’ve got to protect Andy.” The Murdoch company does not admit this sequence of events, including Brooks’s reported comment about “protecting Andy”. It accepts that in 2004 Thurlbeck played tapes of Blunkett’s messages to Coulson, but does not admit that Wallis or Kuttner were involved. It has not yet made any specific comment on Brooks’s alleged reaction to Thurlbeck’s claims.

Scotland Yard and the Press Complaints Commission, the newspaper watchdog at the time, publicly attacked the Guardian’s story and left unchallenged the News of the World’s account. In the background, other victims of the hacking started to follow Gordon Taylor, of the Professional Footballers’ Association, to the civil courts, which started to order NGN to disclose internal records. Inside the company, by the autumn of 2009, Brooks was pressing for “an email deletion policy” to be put into effect.

The evidence suggests that there had been past occasions when the company had ordered the deletion of some emails which were out of date or which were causing problems of some kind. However, the new plan took on a new objective, which was spelled out in a message to Brooks on 30th November 2009: “To eliminate in a consistent manner… emails that could be unhelpful in the context of future litigation.”

NGN stresses that this email also included a requirement that “in the event of actual or prospective litigation all documents which are relevant to the dispute, [sic] have to be retained and cannot be deleted or destroyed, however compromising they may be”. The claimants, however, say that this requirement was “conveniently and blatantly ignored”, and that the subsequent programme of deletions “hindered and prejudiced the criminal investigations… as well as the civil proceedings brought by victims of voicemail interception”.

Beyond that, the company has claimed repeatedly in statements to the High Court that any deletions of email messages “were conducted for commercial, IT and practical reasons”.

With whatever objective in mind, both James Murdoch and Brooks pushed for the deletions to happen. The subject turns up regularly in James Murdoch’s to-do lists and meeting agendas which have been disclosed to the court. Brooks periodically sent emails urging that the deletions should begin. And yet the entire plan ran into a mysterious glitch. Either the IT department was indolent and inefficient, or there were rebels inside the Murdoch company who deliberately defied their orders.

For nine months after the new policy was agreed, the IT department simply failed to act on instructions. By the summer of 2010, Brooks was not only pushing for action, she was demanding even more deletions. On 4th August, Andrew Hickey from the IT department emailed her: “Your note mentions Jan 2010 as the cut-off point. This is different to the December 1 2007 date that we discussed and put in the policy attached herewith. Do you want to implement Jan 2010?” She replied “Yes to Jan 2010. Clean sweep.” She then added an apparent order for discretion: “No company-wide comms.”

It was some five weeks later, on 6th September, with IT personnel still not deleting messages, that Sienna Miller’s lawyer wrote to request the company to preserve evidence. And yet, three days later, a short sequence of emails ordered the IT department to “delete all archived email… pre Jan 2005… Needs to be done by today so please align a resource… There is a senior management requirement to delete this data as quickly as possible”.

By the middle of October, the IT department had complied, wiping out all 4.4m emails that had passed through the servers of the Sun as well as the News of the World before 31st December 2004—thus obliterating the digital footprints not only of Sean Hoare, who had spoken to the New York Times, but of every journalist and every private investigator who had worked for the papers during their first decade of criminal behaviour. The company denies that the deletion of these emails “was prompted by and/or connected to receipt by NGN of the letter of claim on behalf of Ms Miller”, and it repeats that all deletions were done for “commercial, IT and practical reasons”.

Even now, the evidence suggests, the IT department failed to act on Brooks’s continuing reminders to carry on deleting the next five years’ worth of emails. When she emailed the company’s commercial lawyer, Jon Chapman, on 10th October asking for an update on email deletion, he sent it on to Andrew Hickey in IT, adding: “Should I go and see now [sic] and get fired-—would be a shame for you to go so soon?!!! Do you reckon you can add some telling IT arguments to back up my legal ones?”

During that same week, on 7th October, internal records reveal that a news desk administrator took nine boxes of paperwork and tapes that related to high-profile investigations dating back to the mid-1990s—“many of which were the result of unlawful conduct”—and put them in a company archive in Enfield. A week later, they were removed from Enfield—and have never been seen again. The claimants say that “NGN have refused to carry out any searches for them.”

Wave after wave of deletions wiped some 31m emails from the company servers

That same month, all of the computers used by the journalists specifically named in that Sienna Miller letter of claim were destroyed. The Murdoch company admits that this happened, but denies that it was done in response to the letter of claim or to conceal evidence of wrongdoing. Later that year, the company was due to move to a new HQ.

On 15th December, the Guardian disclosed that Miller’s lawyers had evidence that it was the News of the World’s news editor, Ian Edmondson, who had arranged for her voicemail to be hacked. This set off a catastrophic chain reaction within the Murdoch company. Not all of this is clear. One important element may involve the company’s thoroughly conservative external solicitor, Julian Pike, who worked for the Queen’s own thoroughly conservative law firm, Farrer & Co. By this time, as he later admitted at the Leveson hearing, he knew that the company’s claim about the hacking being the work of one rogue reporter was false.

On 10th December, he had responded to Miller’s search for evidence by submitting a statement that the company could not provide any emails for the timeframe of her complaint, because it retained emails for only six months. However, since the IT department had not carried out the instructions it had been given, that statement was incorrect. The one mass deletion had stopped at the end of 2004, so the company still had nearly six years of emails that could be searched. Evidently realising he had been misled, Pike contacted a senior figure in the IT department, Chris Williams, and asked him to check the surviving archive for Mulcaire’s email address.

Senior legal figures in the company intervened, telling Williams to report to them and not to Pike. They may also have reflected that if only the IT department had obeyed orders, there would by now have been no email archive to search. The claimants’ case is that, nevertheless, there was a problem with the search because the mass of Mulcaire’s emails had already been subject to targeted deletions in order to “conceal the extent and scale of the wrongdoing”.

As it was, the new evidence shows that, on the afternoon of 6th January 2011, Williams relayed a small collection of emails: three of them showed Edmondson illegally tasking Mulcaire; others showed two previous news editors, Thurlbeck and James Weatherup, doing the same. The company was now in a very difficult position: disclosing this evidence would shatter the longstanding claim that only one rogue reporter was involved with Mulcaire; but concealing it could run into opposition from Pike. New evidence now reveals the detail of what happened.

On the following day, Friday 7th January, Scotland Yard reacted to publicity over Miller’s claim by writing to the Murdoch company asking for “any material which could be potential evidence of phone hacking relating to Ian Edmondson.” The claimants allege that Brooks opted not to hand over the three messages that implicated Edmondson, in order to have more time to continue concealing and destroying evidence. The company denies this, saying that it wanted to locate “any other material of concern” in Edmondson’s emails. Whatever the explanation, Brooks gave the police nothing and later ordered a new trawl of Edmondson’s messages.

On that same Friday, Brooks spent two hours in a meeting with senior personnel including the two lawyers, Crone and Chapman. According to papers lodged in open court: “The claimants’ case is that the three incriminating emails, as well as the incriminating emails involving Neville Thurlbeck and James Weatherup, were discussed at this meeting and steps then taken to conceal the true scale and extent of the unlawful activities; and that Ms Brooks knew of these incriminating emails and approved a plan to delete emails as a result.” The Murdoch company agrees that there was a two-hour meeting at which the emails were discussed, but denies that this involved any concealment plan.

Over the weekend, a senior IT executive sent instructions that the emails of senior executives were to be deleted from the archive. On Monday, an NGN board meeting agreed to call in an outside contractor, Essential Computing, to start work on the deletions. The company instructed a second outside contractor, HCL, to create a backup of the archive, and then deletions began.

Years earlier, Brooks had taken the legitimate precaution of storing her emails on her computer, not in the online archive. The IT department now removed all the emails from her machine and stored them on a thumb drive. Months later, the Murdoch company surrendered to the police a thumb drive that it claimed contained these emails: it was encrypted; the company refused to help to decrypt it; and it has never been opened.

Brooks had been using her computer for only six months. Later that month, her old machine was taken from her old office and stored. At some point, somebody went to the storage room and removed its hard drive, including its store of old emails. Months later, the Murdoch company surrendered to the police a hard drive that they claimed was Brooks’s. The truth has never become clear. It too was encrypted and the company has declined to provide a key. The company neither admits nor denies that the wrong hard drive may have been given to police, but it denies the claimants’ allegation that Brooks’s computer was “destroyed or lost in order to conceal wrongdoing”.

By this time, a technician from Essential Computing had found that there were no longer any emails in the archive to or from the news editor, Edmondson, or the journalist and specialist hacker Dan Evans. The claimants say that they had been specially targeted for deletion. At some point, Edmondson’s computer had been destroyed. The company denies that this was done to conceal wrongdoing.

Now technicians deleted the emails of the whole top rank of senior executives. By Tuesday 18th January 2011, they had wiped from the online archive all emails sent and received up to the end of 2008 by the executive chairman, James Murdoch; both of his PAs; the former chief executive, Les Hinton; managing director, Clive Milner; and company lawyer Jon Chapman. According to the claimants, this “had the deliberate effect of erasing emails to and from senior executives at a critical period when unlawful activity was rife”: it was, they claim, “a wholly cynical act of concealment”. The claimants do not allege that all of those whose emails were deleted were involved in crime or cover-up.

The Murdoch company says that by this time any email deletions were part of a long-term plan to shift the company’s data to a new system. It admits that the emails of senior executives were deleted but says that “that was entirely normal and conventional in line with the aim of demonstrating to employees that their managers had migrated to the new system”. It adds that if Brooks’s emails were removed from her computer, this was being done for all employees as “part of general good industry practice to ensure that they could not be copied remotely”.

The thumb drive was encrypted; the company refused to help decrypt it; and it has never been opened

The technicians went on to delete from the archive all emails sent and received by a list of employees, past and present, who were thought to have been involved in crime. On 13th January 2011, the list of possible suspects, which was supplied by Brooks’s new right-hand man, Will Lewis, named 13 people. Over the next seven days, it grew to a total of 105 individuals whose electronic footprints were wiped from the archive. It is important to say that some of these messages were saved on a laptop, although there is a continuing dispute about how many finally survived. (On this dispute, more below.)

Whatever the intention, the new evidence suggests that the potential effect of this week of frantic activity was that, by 21st January, police could search the email archive and find that a mass of potentially important information about the activity of senior executives—including Brooks—and the 105 possible suspects—specifically including Ian Edmondson—was no longer there. That day, Coulson resigned. Brooks had met him the previous week at what she described as a “discreet” location.

And then they waited. The pressure was extreme. On 23rd January, a senior executive emailed Brooks with a report of bad press coverage on the hacking. She forwarded it to Lewis, adding simply “Christ.” But there was a reason for waiting, which became clear on 24th January, when Rupert Murdoch flew into London to take charge. That morning, Brooks had sent an email to a close friend indicating that she was going to give the full facts about the scandal to Murdoch and that Lewis and his close associate, Simon Greenberg, were then going to brief him on the company’s strategy.

On the following day, the company sacked Edmondson and told Scotland Yard that it would pass over the three emails that incriminated him. It told the Yard nothing about the other emails it had that implicated Thurlbeck and Weatherup. It also successfully pretended that they had only just discovered the three emails, whereas the new evidence shows that it had held them back for nearly three weeks, during which time it cleared the archive of sensitive messages. On that same day, the company began to delete a great many more emails.

As the three messages involving Edmondson were handed to police the next day, technicians finished wiping from the archive every email sent or received by every employee via the company servers in 2005 and 2006. In those 48 hours, they deleted an estimated 11.1m emails. This followed the exercise the previous autumn that had removed everything up to the end of 2004. The entire history of the News of the World’s criminal behaviour up until the arrest of Goodman and Mulcaire in August 2006 had now been deleted. The fact that Rupert Murdoch was in London and had apparently been briefed about strategy clearly raises the question of whether he approved of this extra phase of destruction, even as police were finally called in.

On 26th January, Scotland Yard set up Operation Weeting to re-investigate the whole saga. On 27th January, Burton Copeland, solicitors for the Murdoch company, wrote to offer the company’s “ongoing co-operation”. On 28th January, the solicitors sent a second letter specifically offering to search for material relating to Edmondson from 1st January 2005 to 31st August 2006—which had been deleted earlier in the month. Without a trace of irony, the solicitors warned: “There can be no absolute guarantee that all the material that was created in the relevant time period remains.”

Operation Weeting now told the Murdoch company formally that it would need access to 10 years of the entire electronic archive from 2001. For a few days, there was no reaction in the company. An email records that there was an order “from the top” to the IT department to pause any deletions—until 3rd February, when Lewis told them to continue with the “email migration process”. This involved one more layer of destruction.

On 7th and 8th February, acting on the company’s orders, the outside contractor, Essential Computing, deleted every message sent or received in 2007—15.2m of them. From whatever motive, the entire history of the News of the World’s cover-up after the arrest of Goodman and Mulcaire had now been wiped from the archive while the company knew that Operation Weeting was waiting to get access to its electronic records.

On the morning of 9th February, the company’s delivery manager, John Morris, emailed Essential to check that all of the deletions had taken place. That afternoon, senior executives held their first meeting with Operation Weeting and, according to a police record which has now been disclosed, they told the police that “no data” had been retained by the company from before 1st January 2008. They did not explain that less than 24 hours earlier they had been deleting the whole year of 2007; nor that in the past five months they had destroyed everything from the years before 2007.

At this point, the company still had a backup of the email archive, which it had asked the outside contractor, HCL, to make at the beginning of January. In the following week, according to a police statement by a Murdoch IT worker, the company destroyed those backup tapes. The company admits that the IT worker told police that the backups had been scratched “so that there were none available to be physically stolen”.

The final result, the evidence suggests, was that, led by Brooks and Lewis, with Rupert Murdoch supervising, the company had moved through several stages of escalating destruction that coincided with the possibility of police action coming closer: it had now deleted from the archive all emails up to the end of 2007 for all employees, past and present; and all emails up to the end of 2008 of all senior executives, including James Murdoch and Brooks; and all the emails of all the suspects apart from those that may have survived on the “extraction laptop”. Since Sienna Miller’s lawyer wrote to the company in September 2010, requiring it to preserve evidence, it had destroyed a total of 30.7m messages. A clean sweep.

With Rupert Murdoch still trying to complete the takeover of satellite broadcaster BSkyB—his biggest ever deal—the company’s promised “ongoing co-operation” with the police began to run into problems.

By 21st April 2011, according to the claimants, the company had handed over only 51 emails, and the operational head of Weeting, detective superintendent Mark Ponting, was “concerned about attempts to pervert the course of justice”.

There had also been two incidents when Weeting had arrested journalists only to find that solicitors from Burton Copeland had seized and concealed the computers and other material from their desks. (The Solicitors Regulation Authority, we now know, later fined two of these solicitors a total of £15,000.) By late May, Weeting had started to hear about the email deletions. In late June, there was an unexpected development.

At a meeting between Weeting detectives and the company’s IT specialists, the technical director from Essential revealed that, back in January—just before the escalating programme of deletions began—they had made backups from the archive. Extensive ones. This was too late for everything up to the end of 2004, which had been destroyed in September 2010. But, if the backup had been successful, they could potentially restore many of the messages from January 2005 to the present day. One of the detectives later said in a statement that the head of the Murdoch IT department, Paul Cheesbrough, “appeared to be totally shocked by this development; it felt as though the cat had been let out the bag.”

While technicians now set about the long and tricky task of restoring the email archive, Weeting confronted Murdoch executives over the original decisions to destroy it. On 8th July, Lewis met them with a strong defence: it was not just that the company servers were so overloaded that they had to delete this mass of material; they also had a more urgent motive. He then told detectives that a confidential source had warned them that a Labour sympathiser inside the company was stealing Brooks’s data and trying to sell it to two Labour politicians who were agitating about the phone hacking: Tom Watson and Gordon Brown.

The claimants say that this story was “obviously baseless and a bad excuse for deleting evidence”. Lewis produced an internal email chain showing that the allegation had first been made on the evening of 24th January 2011, after Rupert Murdoch had arrived in London to be briefed on strategy. This was some days after the IT department had finished deleting all of Brooks’s emails, as well as those of senior executives and suspects. Claimants also noted that nobody from the Murdoch company had mentioned this alleged plot until after detectives discovered that millions of emails had been destroyed. Weeting also discovered that the email chain that started on 24th January had included a senior IT executive saying that they had asked outside consultants to investigate the alleged leak to Watson and Brown, to which Lewis’s close associate, Simon Greenberg, had replied: “Let the game begin.”

Evidence suggests the company had moved through several stages of escalating destruction

This is not the only allegation that the Murdoch company laid false trails to be found by police in order to justify or disguise the destruction. Despite executives setting out an official policy in writing to preserve all documents that might be relevant to future litigation, “however compromising they may be”, in practice, as above, Brooks went ahead and ordered her IT department to make a “clean sweep”, deleting every message up to January 2010. (It is, in any event, not clear how it could be possible to preserve documents for future litigation when the company did not know what future litigation might occur.)

Brooks also ordered the IT department, in January 2011, to conduct a new search of Edmondson’s emails to help the police. Against this, internal messages disclosed in court reveal that when senior technician Chris Williams, acting on company instructions, tried to carry out the search, he found that another senior technician also acting on company instructions, Chris Birch, had already deleted all of Edmondson’s emails up to the end of 2009.

The truth has yet to be established with regard to one trail of particularly important evidence, which turns on the significance of the emails from Lewis in January instructing that the messages of 105 suspects be copied onto a laptop before they were deleted from the archive. The company says that this was an attempt to preserve evidence for the police, even though the email archive was being deleted. The claimants say it was a false trail, aimed at giving the police a “limited pool of data” that was intended to be the only source on which they could draw.

In a police statement, the Essential Computing technician who was given the job of copying the suspects’ emails, says that he warned a Murdoch IT executive that, having extracted the mailboxes of the suspects from the archive, they had failed to make copies of them all. “I verbally warned… that due to the high number of failures during extraction that those emails would never become available again… He did not want to take the advice and insisted that he wanted to delete.” The Essential technician then refused to delete them. “I told him that he would have to execute those jobs and take responsibility for it… Later that afternoon [the technician] came over and wanted the deletion completed in the afternoon, so we purged (he pressed the button) all the data for the mailboxes.”

The claimants say that only a “very limited” number of the suspects’ emails were actually copied; and that those that were copied were then subject to “extensive further manual deletions”, with the result that many emails that were likely to be most important for the police were destroyed. The company agrees that some messages were deleted from the laptop, but it says that these had no evidential value, and that the purpose of this “extraction laptop” was precisely to gather and protect material to help any police inquiry. Both sides agree that some or all of the messages that had survived were copied onto a hard drive which was handed to external consultants for the police to search. Exactly what they found there remains unknown. And exactly what then happened to the laptop also remains a mystery.

In mid-July, Weeting arrested Brooks and spent several days searching parts of the Murdoch building. The new material discloses that they seized 125 items used for office storage and placed them all in a secure area under the supervision of Lewis and Greenberg. It was several weeks before detectives completed a detailed search of all the equipment, at which point they discovered that only 117 of the items were still there. Eight filing cabinets that they had seized from the offices of the editor, Colin Myler, and the managing editor, Bill Akass, had been removed. Nobody from the Murdoch company had alerted them to this. The claimants allege that the company has rejected multiple requests to look for them. They have not been recovered.

During the same search, officers went into Brooks’s office and found that she had a private dressing room with a vanity cabinet. They moved the cabinet and found the door to an underfloor safe. When they opened it, they found it was “filled with hard drives and computers”.

One laptop turned out to contain copies of many thousands of emails from key personnel, some of which proved to be very damaging. One of them had been sent by Coulson when he was still editor, with a crude instruction to deal with a problem with a story about Calum Best: “Do his phone.” That message became part of the prosecution that put Coulson in prison. It also contained an email from Thurlbeck with the transcripts of voicemail messages intercepted from the phone of Gordon Taylor. That became part of the prosecution that put Thurlbeck in prison. This laptop may or may not have been some version of the extraction laptop. In a statement, claimant lawyers said: “NGN has provided no explanation as to why the office underfloor safe of Mrs Brooks contained this laptop with… thousands of emails from key executives, editors and journalists who were implicated in widespread unlawful activities, including criminal activities, and the cover-up and concealment of the same.”

The material from the underfloor safe joined the other sources from which Weeting was trying to restore the lost archive: the backup made by Essential; thousands of emails that detectives found on the home computers of journalists and private investigators they arrested; and hard copies of messages that had been printed out and left in offices which they searched. The attempt to restore the archive was only partly successful. Of the 30.7m emails which had been deleted, only 21.7m were recovered. Around 9m messages—more than a quarter of the archive—were lost for ever.

The response

A spokesperson for News Group Newspapers, a Murdoch company, said:

“In 2011, an unreserved apology was made by NGN to victims of voicemail interception by the News of the World. Since then, NGN has been paying financial damages to those where either there has been wrongdoing (in the case of the News of the World) or for good commercial reasons in the case of allegations against the Sun where liability is not accepted.

These proceedings have now been going on for over 15 years and NGN is seeking to bring them to a close. Between 2011–2015, a large-scale police investigation resulted in the trials of many individuals in the criminal courts. Corporate liability was also investigated at length and, in 2015, the Crown Prosecution Service concluded that there was no evidence to support charges against the company.

The claimants have [now] sought to introduce accusations to the civil court against many current and former journalists, staff and senior executives of News International in a scurrilous and cynical attack on their integrity. Some of these allegations date back to events now 30 years old and relate to allegations which are irrelevant to the matters which are now in issue between the parties. Many of these have been investigated in depth on previous occasions.

These allegations have nothing to do with seeking compensation for victims of phone hacking or unlawful information gathering and should be viewed with considerable caution not only in relation to their veracity but also in the light of those who are behind them. Lawyers for the claimants work with a group of former phone hackers and employ anti-press campaigners and activists who seek to use the compensation claims to make allegations in circumstances they are protected in doing so [sic] by open justice principles.

[The latest accusations] are irrelevant to the fair and just determination of claims.”

*

News Group Newspapers was given the opportunity to respond in more detail to Nick Davies’s reporting ahead of publication; instead it offered the short general statement above. Following the release of most of Davies’s articles, the company responded in a further statement:

“The allegations in this series of articles are in large part contained in draft amendments to the Claimants’ case in their ongoing litigation against News Group Newspapers. The Claimants have applied to introduce these amendments into their pleaded case, but that application has not yet been decided by the Court.

As a result, NGN has not yet pleaded its response to those allegations. If the Claimants are granted permission to make these amendments, NGN will set out its response to them in its Defence to be served at a later date.

This series of articles therefore is entirely one sided and misleading and should be viewed with considerable caution.”